Preface to Filmmakers Statement (2019)

Shared History was first broadcast throughout the country on PBS Plus almost 15 years ago. I began the effort to document the historical relationship between my family and African America families connected to Woodlands Plantation in 1993. Edward Ball’s book, Slaves in the Family, which was about the massive slaveholding legacy of the South Carolina Balls, had just been published. It reawakened memories of old white families in South Carolina to a heritage that many of their ancestors were connected to black families by blood or land—historical facts that they did not want to be reminded. That was over 25 years ago. It is almost commonplace now for white and black families connected through slavery to link with each other today—many with the help of Coming to the Table. There is a more open attitude now among whites about providing family records to African American families and even helping with the research to identify particular enslaved people. Some have started to hold reunions like the one shown in Shared History. African American families seem more open to investigating the horrific details of their past. But even as the genealogical tools have become more sophisticated, researching black family history is still extremely difficult because the first federal census that included black people with their names and locations was not published until 1870. Still, there are many success stories.

We, as a nation, are only beginning to acknowledge the impact of slavery on our world today—our nation was built on the backs of slaves, free labor that created an unparalleled economy that benefited the entire world. However, since making Shared History, I have to acknowledge that not much has changed—African Americans lag behind in almost every economic measure and racial hatred is again being fueled by the politics of blame and suspicion of otherness. The pie continues to be divided unequally even though there is enough for all. But after all this time, the story of Shared History still holds out for the possibility that as people share their history with others, new personal and family relationships are brought to the surface with realities that prove we are more alike than we seem.

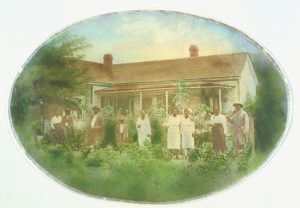

I had always known that my ancestors were slave owners; in fact, I had interacted with the descendants of the enslaved people from Woodlands Plantation throughout my childhood when my grandmother took me and my cousins to the plantation for visits. It was not until I was much older that I realized that the longevity of our families’ connection might be unique, yet might also illustrate an undercurrent in the common culture of the United States.

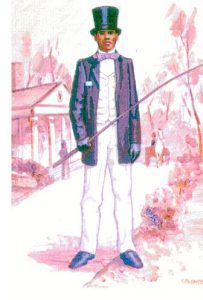

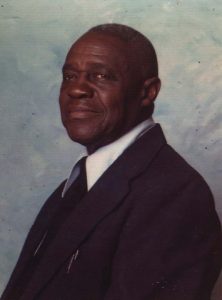

In 1993, during a meeting of my family about the preservation of the plantation house, Junior Manigault dropped by to say hello. Mr. Manigault, who died in 2007, was descended from Jim Rumph, a slave who was owned by my ancestors. He was born in African in 1810 and died in 1922 at Woodlands at the age of 112. Jim Rumph, his son and grandson, all of the same name, had been the caretakers of Woodlands over a span of one hundred years. Mr. Manigault became somewhat of a caretaker of the property too. He worked for the county highway department but also raised pigs across the road on property his grandfather had bought from the Simms family. He and my hunting cousins had a deal with Junior: he would use some of the fields at Woodlands without cost to plant and harvest corn to feed his pigs and, in return, my cousins would benefit because the gleanings would attract deer and birds for hunting. In the moment of Junior’s visit, I was struck by the continuity of our families’ relationship and decided to look more deeply into our connection that had lasted for over 260 years. I wondered if our families—descendants of the enslaved people of Woodlands and my white family—could come together to confront the realities of our shared history.

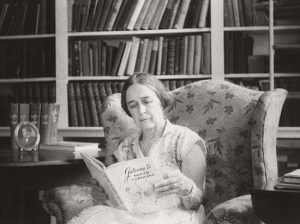

I am descended from William Gilmore Simms, a 19th-century American writer. Simms was one of the principal apologists for slavery in the debates leading US in 1860. My grandmother, Mary C. Simms Oliphant, an apologist for segregation, was an historian and author. She had told us that our ancestors had been “good masters,” a story that helped me assuage the discomfort I felt as a child about my family’s slave-owning past.

I began Shared History to document the history of the relationships between my family and the descendants of the enslaved people of Woodlands before those who remembered passed and their stories were lost. I wanted my nieces and nephews, the inheritors of Woodlands, to not only know this history, but also to fully appreciate that the continued ownership of Woodlands by our family had been made possible by the descendants of the former slaves who stayed at Woodlands after the Civil War and cared for the property. I wanted them to understand it was not so much the old relationship with our family that made the African American families seem attached to Woodlands but the fact that it was their ancestral home too and that we should respect their claim on this property. The development of the project ultimately forced me to come to terms with our ancestors’ participation in slavery and our own responsibility to acknowledge our particular attitudes and behaviors related to race today.

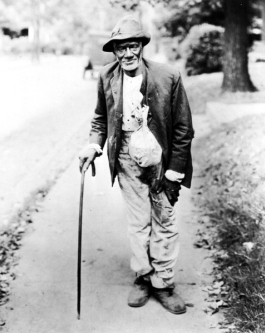

After the first of many conversation with my mother, who, as a child, had lived off and on at Woodlands, I combed through the boxes of my grandmother’s files in my mother’s attic labeled “Woodlands” and found a photograph of an ancient black man that I found out later had been taken by my grandfather in about 1921. My mother said the photograph must be of a member of the Rumph family and that I should contact Junior Manigault’s sister, Dorothy Manigault to see if she could identify it. Dorothy was the scribe of her community and had kept us up-to-date with news about her family and others connected to Woodlands. She lived on the Rumph property—where Junior raised his pigs. She showed the photograph to her aunts who told her it was Jim Rumph, the Jim who had been a slave at Woodlands.

Dorothy became my friend and helped me navigate matters of family, church and community—I’m sure with some degree of trepidation. Without her help, I would never have been able to approach the descendants of those enslaved at Woodlands. I am deeply grateful for her help and friendship.

I met Rhonda Kearse, Dorothy’s great niece, a few years later. Her grandmother introduced us at a “homecoming” event I hosted at Woodlands in 1996. Rhonda, who has lived in New Jersey all her life, is an architect with the Port Authority of New York/New Jersey. She agreed to be part of the project and to help create a reason for our families to come together. On November 24, 2001, we held the “Woodlands Families 50th Anniversary Gathering” to commemorate a similar event in 1951 held on the plantation grounds. It was then that we met Charles Orr, who had found us at www.sharedhistory.org. Charles, a social work administrator in Detroit, Michigan, is the great grandson of Isaac Nimmons, the slave coachman who left after the Civil War. The three of us agreed to work together to break the silence mandated by the old etiquettes created by our ancestors and start a different kind of conversation—one that used our historical relationship as a base from which we could discover and reconsider the realities that might genuinely connect our common backgrounds.

Shared History is our story and the story of our country’s continuing struggle to address the realities of our past.

Felicia Furman, Producer/Director