As a documentary, Shared History produced hours and hours of footage that could not be included in the final film. (This footage is located in the Shared History Collection at the South Caroliniana Library in Columbia, South Carolina.) However, a number of videos were created from this footage that give the viewer more information about the making of Shared History and feature interviews with many of the Woodlands families and others that do not appear in the final film but nonetheless are important for historical record and interesting storytelling.

At the Beginning is about how and why Shared History was made and the significant role Mr. Earthlee Rumph (1907–1993) had in making the film, although he died on the day I met him. He was nearly a folk hero in his community and family—perhaps playing the role of the mythological trickster. At a young age, he went to New York and worked in the construction business and bought a car. He returned often to Bamberg and on his return trip to New York he would carry young people from the Bamberg community to New York to settle with aunts or Bamberg neighbors who had already made their way there for better opportunity. You might say that Earthlee had his own private underground railroad, taking his people to a better life. He was an admitted rogue and storyteller. He “ran” cigarettes from South Carolina to New York where he could sell them for a cheaper price. Using his business “sharps” he made a life for himself and helped others break out of the cycle of picking cotton. One of the men in the Simms family who wanted Mr. Rumph to sharecrop for him said “Earthlee thinks he’s smarter than I am.” He was. It clearly irked the Simms family that he wouldn’t farm for them, and they considered him lazy. Despite all of his notoriety, Earthlee replied that, “I was the ‘workin’ist’[sic] one.

Scholars at Woodlands—The morning of the 2001 50 Anniversary Woodlands Family Gathering, three of the academic scholars for the project, Jualynne Dodson (Michigan State University), Karen Fields (independent scholar) and Walter Edgar (historian), whose work was funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, came together to reflect on the major themes revealed in the research they were undertaking for the project. They were there to witness the coming together of the black and white families of Woodlands Plantation 50 years since my grandmother had assembled the ancestors of the people who had been enslaved by the Simms family. Many attending had been children during the first event. Although reunions of this sort were rare before Shared History, the black and white families didn’t seem to think it was unusual but wondered why we hadn’t done it sooner. The scholars meeting on the side porch of the old house consider what had made it attractive for almost 200 people, many who had traveled great distances, to be there.

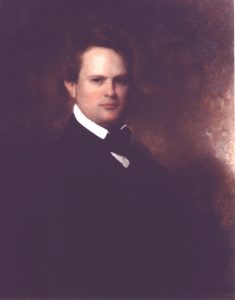

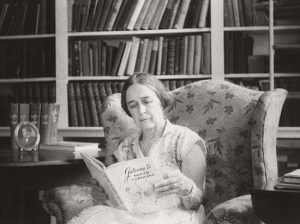

SCETV 1967 Television interview of Mary C. Simms Oliphant (1891 –1988). For many years, Mrs. Oliphant, my grandmother, wrote the history and civics books taught in the public schools of South Carolina, which left out the role slavery and African Americans had had in the history of South Carolina. Although she was beloved by many children in the state, African Americans were brought up believing they had no history and many continue to feel the negative impact of her books today. (23:09)

Tribute to Llewellyn Rowe Hopkins (1902 – 1987). Llewellyn Rowe Hopkins was a member of the Rowe family of Woodlands. We can speculate that her people were probably in South Carolina before the Revolutionary War because her last name is the same as my white pre-revolutionary ancestor, Michael Christopher Rowe, who owned land near Woodlands. Llewellyn lived at Woodlands plantation with her parents until she was a teenager. Her father share cropped for my grandmother. Llewellyn’s daughter told me that her mother didn’t want a life of picking cotton. So at some point my great grandmother trained Llewellyn to be a maid and to everyone’s astonishment would proudly explain that, “I gave Llewellyn to my daughter as a wedding present—a preposterous statement that defied the demise of slavery. Llewellyn was then sent up to Greenville, SC, to work for my grandmother, Mary C. Simms Oliphant. The young Llewellyn married Mr. Hopkins in Greenville and raised several generations of Simms children. She sent her own children back to the plantation for her parents to raise. She was a petit dark woman who would explain to my grandmother’s house guests, that she had been with the Simms family since before slavery. She told fantastical stories based on Brer Rabbit that could challenge the drama of movies of today like Game of Thrones and the many Star Wars films. However, she could not read or write despite efforts by my grandmother to have her tutored. Llewellyn worked for my grandmother until she died. She is buried in the Simms Cemetery on the plantation.

Junior Manigault (1925–2008)—Making Syrup. Every year near Thanksgiving, the Rumph family would gather to kill hogs and make syrup. They were one of the few families that still grew a little cane and had a mule drawn cane crusher. Days would go by as the dark syrup bubbled in the pan in the little house. If invited, you might find yourself led to the roiling pot from the light of the embers. This video takes you through the process and shows neighbors black and white coming by with their mason jars to test the largess of Junior’s generosity. It would be the last year of the event and many people wanted a jar.

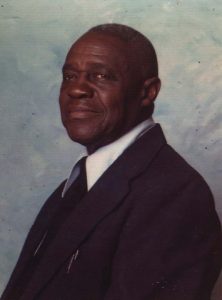

Junior Manigault (1925–2008)—Planting by the phases of the moon . Mr. Manigault used traditional methods of farming passed onto him by his mother Llewellyn “Mudd” Manigault. In addition to being on the county highway construction team and a Deacon at Pilgrim Baptist Church, Junior raised pigs on land across the road from the Simms plantation—land his grandfather had bought i1917. (See film for a decades-long misunderstanding about how the Rumph’s secured the land where Junior grew his pigs.) The day of the interview it was hot and thick but he was almost finished with planting his feed corn and I waited on the side porch. He had come over to Woodlands to check on his corn crop. My male cousins were hunters and Junior had a deal with them. Junior would plant corn on their land and the leavenings would “seed” the field for their corporate clients to ensure a good hunt. So here was a cooperative relationship between the descendants of the enslaved and slave owner that seemed to work for them both—a new kind of business deal around land.

I had promised Junior a glass of lemonade (real lemonade) if he would let me interview him about planting by the signs of the moon. Junior’s accent is mellifluous—somewhere between Charleston drawl and a Gullah tune. He would use a phrase I grew up to describe a waning moon—it was a lee little moon, “When the moon would become a new moon,” he said, it’s “a lee little moon” and it would be time to rest. See what else Mr. Manigault has to say about this traditional way of planting the next time you plant a garden.

Thomas Rumph is a tall man and a dapper dresser. He had worn a fine suit for our interview. It was in the fall so the oppressive heat had somewhat lifted. I had gotten to know Thomas through his half-sister Dorothy Manigault. Dorothy had told me that his father was in his seventies when he married Thomas’s mother, she being only 14 or 15. That was Maizie Rumph. When children came along, there were lots of confusions about who the uncle was and who the nephew was, etc. because the age difference was so great. Eventually, Thomas and his brother struck out for Augusta, GA and got jobs in the new nuclear weapons plant.

The interview went well, and we were relieved it did not require multiple takes, because the buzzing black flies had found us in the woods. There were a few times though that I thought Mr. Rumph was a bit too generous to my family—the slave owners. We were on property that Mr. Rumph’s family had farmed during and after slavery and it was killing me that Thomas didn’t denounce my ancestor and his role as master. But I suspect if you look and listen closely there are a few masterful verbal gestures and a flick of the eye that might indicate what he was really thinking.

We were at a Woodlands house party. My sisters came down to help and we had members of the Rumph family staying for the weekend. Boy, was that a first. The only time their ancestors had been in that house was to cook and clean so we were all a little nervous. But the first evening proceeded as any festive night should with stories about our lives and how we got here today.